Organize software delivery around outcomes, not roles: continuous delivery and cross-functional teams

Published 18 December 2011Translations: 中文

When implementing continuous delivery, it's easy to focus on automation and tooling because these are usually the easiest things to start with. However continuous delivery also relies for its success on optimizing your organizational structure for throughput. One of the biggest barriers we at ThoughtWorks have seen to continuous delivery is teams organized by role or by tier, rather than by business outcome. In this post I'll address the root cause of this problem, and how to overcome it.

The Devops movement emerged from a frustration with the engineering, testing, and operations silos that have been created in IT organizations. Why do these silos exist? There is a quote from Coleen Young of Gartner that cuts to the core of this issue:

Virtually every IT organization must face a process transformation [which will] inevitably drive radical changes in organizational structure. Traditional IT service delivery and organizational models achieved efficiency at the expense of effectiveness. [At one time when computing was expensive and resources were scarce] it made sense to maximize the utilization and life cycle costs of assets... This approach to resource orchestration inevitably resulted in functional silos. The optimized process-based organization is horizontally focused on outcomes, not vertically oriented around skills1.

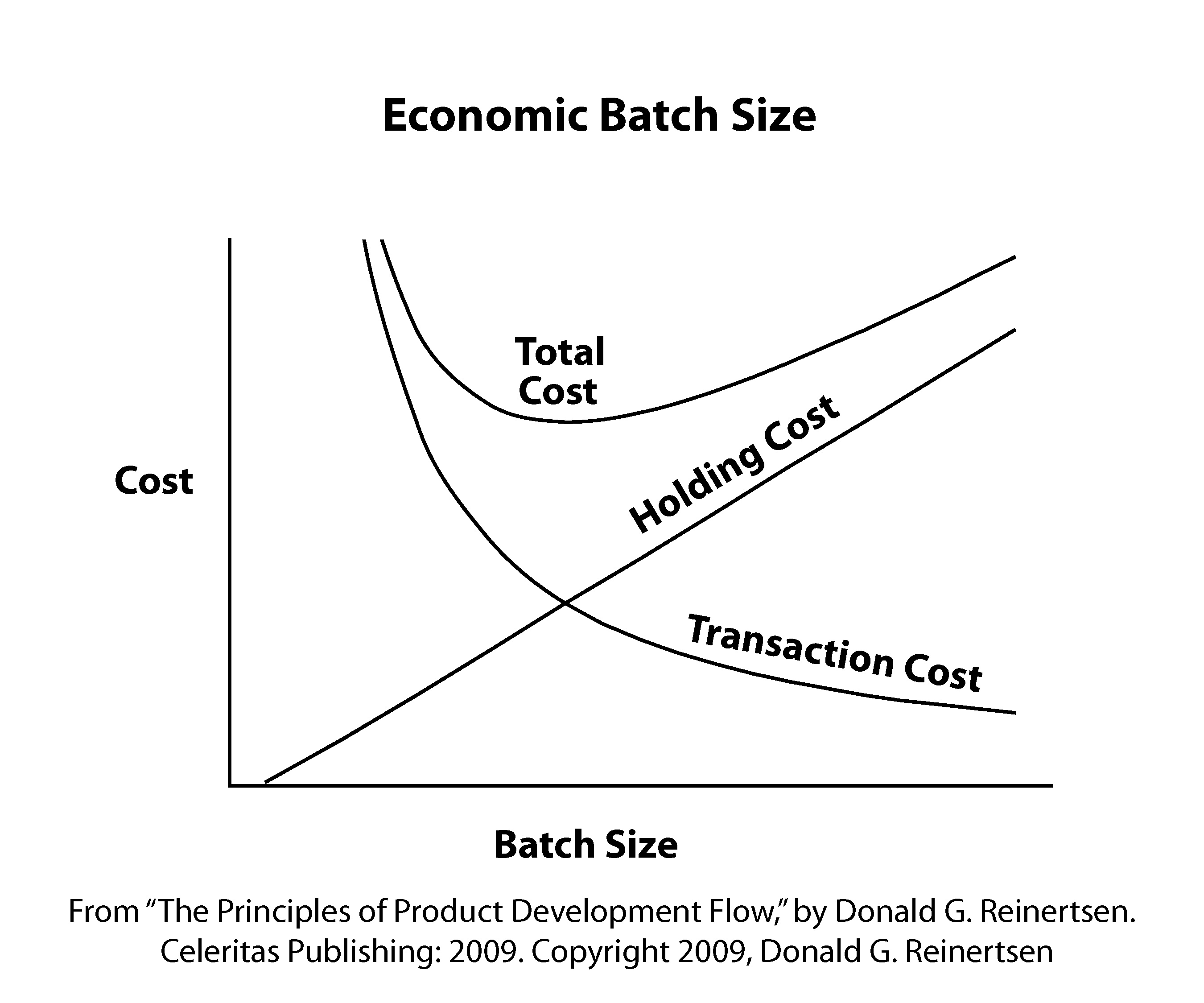

Creating silos is a rational response to the historical expense of computing resources and the high transaction cost of putting out a release. There is a direct relationship between batch size and this transaction cost, expressed in the Economic Lot Size equation which governs the trade-off between the transaction cost--the cost of sending a batch to the next process (say from development to testing)----and the holding cost---the cost of not sending it. This is discussed in Donald Reinertsen’s book, The Principles of Product Development Flow (my favourite IT book of 2009)---which contains Figure 1, below (p35, discussion p121):

[caption align="aligncenter" width="350" caption="Figure 1"] [/caption]

[/caption]

Continuous delivery: reducing transaction cost

In the mainframe era, the transaction cost of putting out a release was small. But as we moved first to client-server systems, and thence to web-based systems, the transaction costs of testing and releasing software became much higher, providing by far the biggest contribution to total cost. This drove up batch size and resulted in the silos we see today.

But the message of continuous delivery is that we now have the tools, patterns and practices to drive down the transaction cost of releasing a change enormously---to the extent that holding cost is actually a much bigger contribution to the total delivery cost.

Given this, one key rationale for creating organizational silos no longer holds. And since silos lead to lower software quality, lower production stability, and less frequent releases, there are many good reasons to get rid of them, at least for teams working on strategic projects2.

Cross-functional teams: optimizing for throughput

The alternative to silos is cross-functional teams, in which (as Young suggests) we optimize for throughput---or lead-time. By implementing the practices of continuous delivery, we reduce transaction costs to a negligible level. Next, we create very small batches of work by limiting work in process and focus on getting that functionality either released to users, or at least releaseable to users, in the shortest time possible.

Cross-functional teams are not a new idea, but their importance is often under-estimated. Having a cross-functional team is a vital ingredient for reducing lead-time because much of the delay getting functionality released is incurred through communication overhead. When everyone involved in the delivery of a product or service is co-located, developers can call over testers and show them what they’ve been working on so that they can get fast feedback, testers and developers can collaborate on creating functional acceptance tests, developers can discuss proposed schema changes with dbas before they make them, and architectural trade-offs can be discussed with an infrastructure expert before any code gets written.

This not only makes software delivery much faster, but also much more fun. And of course we end up with higher quality software, lower-risk releases, and much faster responsiveness to our customers. These considerations were key in Amazon's decision to move to a service-oriented architecture with cross-functional teams.

There are a couple of common objections to cross-functional teams. One is that it is prohibited by a control known as segregation of duties when your organization is subject to regulations such as Sarbanes-Oxley and PCI-DSS. In fact, segregation of duties can be implemented more effectively within cross-functional teams, as described in an article I recently co-authored for Cutter IT Journal (registration required).

Annother objection is the additional cost of creating cross-functional teams and implementing continuous delivery. This is true, which means that you only want to incur this extra cost for the part of your service portfolio that is strategic. The additional cost in this case is paid back many times by the benefit of getting to market faster, learning from your users and iterating rapidly, and avoiding building functionality that is not useful (the biggest source of waste in software development).

How should organizations move to a cross-functional model?

If you have a small IT organization, say less than thirty people, you can move to a cross-functional model in one go. With larger organizations, as with all things in continuous delivery, you should proceed iteratively and incrementally.

Start with a pilot product. Make sure you’re measuring total cost and revenue delivered over the lifecycle of the product, in addition to metrics such as cycle time and the incremental value delivered by every new release. The team will need to own the SLA for the service, and crucially should be able to self-service their own infrastructure, including testing and production environments, without having to wait days or weeks for hardware to be provisioned. The team should be given plenty of time to implement continuous delivery, and focus on delivering a minimum viable product and then iterating rapidly in response to real data from users.

Large organizations with distributed teams are actually a great target for moving to a cross-functional model: the key here is simply to ensure that teams are not grouped by role. Nothing kills continuous delivery of high quality software faster than having a development team in one country, a testing team in another, and the operations team in a third.

Finally, teams should focus initially on verifying their business hypothesis by devising the smallest possible minimum viable product to test it, and pivoting in the case of failure.

Thanks to Don Reinertsen for permission to use figures from his book, The Principles of Product Development Flow. Thanks to Don Reinertsen, Pat Kua, Dutch Steutel, Dennise Openshaw, and Chris Hilton for feedback on an earlier draft of this post.

1Colleen M. Young, "Six steps to process-based IT organizational design", Stamford, CT: Gartner, 2006, via Steve Bell, Enterprise Agility (forthcoming).

2Note that some of the problems of silos can be mitigated through better management, such as ensuring resources within silos are not excessively loaded, and rotating people through different groups to encourage collaboration and understanding.