Continuous Testing

The key to building quality into our software is making sure we can get fast feedback on the impact of changes. Traditionally, extensive use was made of manual inspection of code changes and manual testing (testers following documentation describing the steps required to test the various functions of the system) in order to demonstrate the correctness of the system. This type of testing was normally done in a phase following “dev complete”. However this strategy have several drawbacks:

- Manual regression testing takes a long time and is relatively expensive to perform, creating a bottleneck that prevents us releasing software more frequently, and getting feedback to developers weeks (and sometimes months) after they wrote the code being tested.

- Manual tests and inspections are not very reliable, since people are notoriously poor at performing repetitive tasks such as regression testing manually, and it is extremely hard to predict the impact of a set of changes on a complex software system through inspection.

- When systems are evolving over time, as is the case in modern software products and services, we have to spend considerable effort updating test documentation to keep it up-to-date.

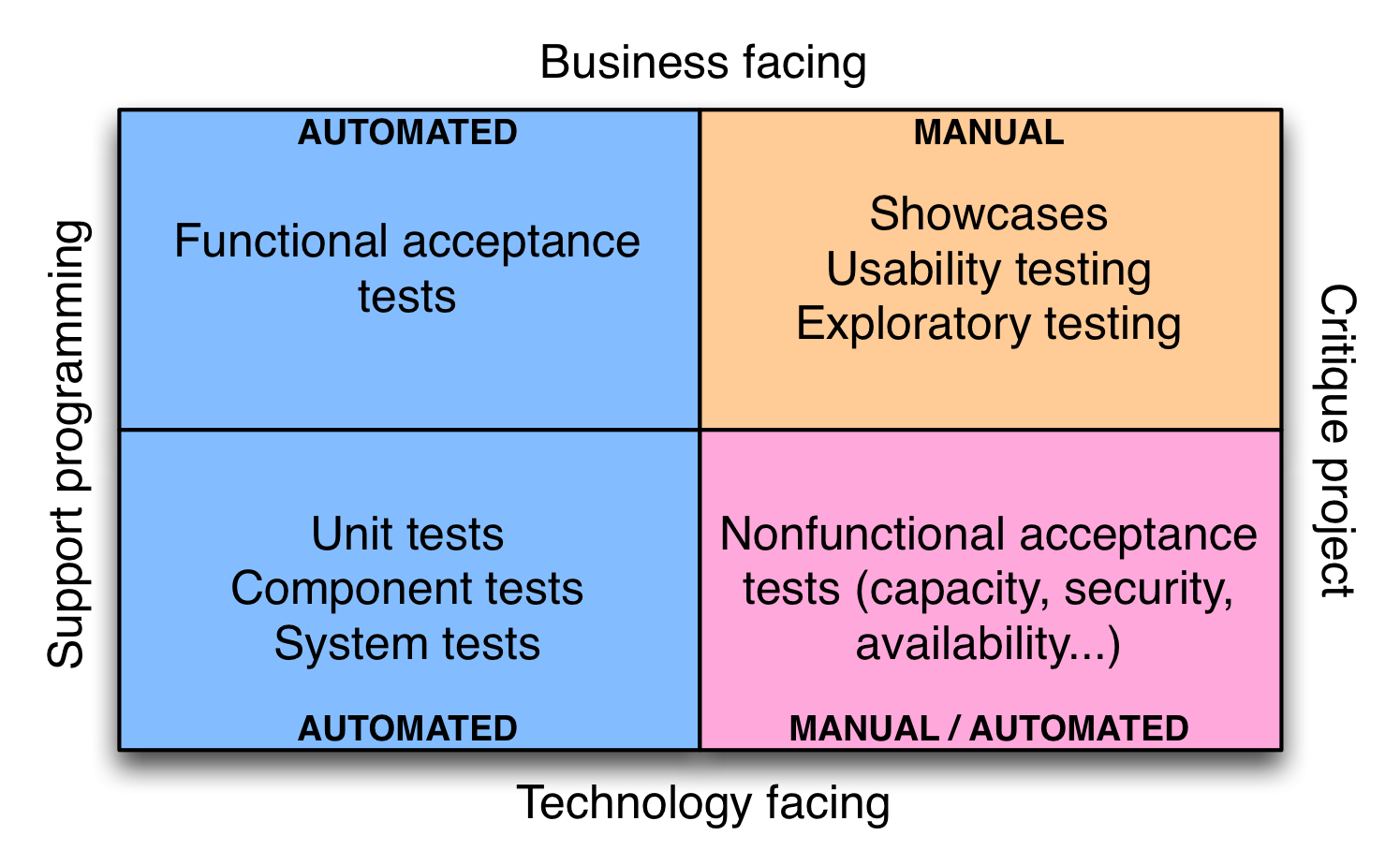

In order to build quality in to software, we need to adopt a different approach. Our goal is to run many different types of tests—both manual and automated—continually throughout the delivery process. The types of tests we want to run are nicely laid out the quadrant diagram created by Brian Marick, below:

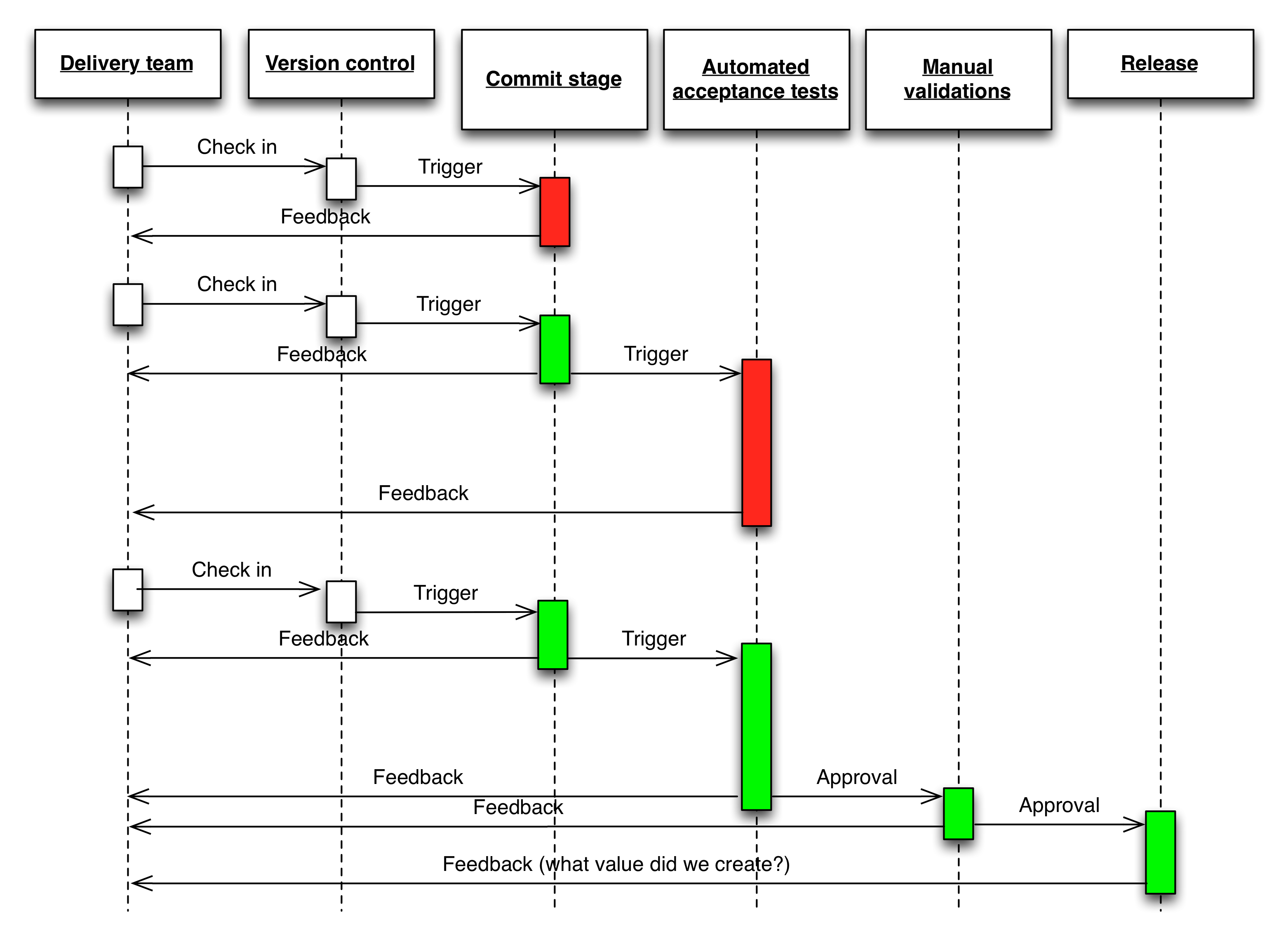

Once we have continuous integration and test automation in place, we create a deployment pipeline (the key pattern in continuous delivery). In the deployment pipeline pattern, every change runs a build that a) creates packages that can be deployed to any environment and b) runs unit tests (and possibly other tasks such as static analysis), giving feedback to developers in the space of a few minutes. Packages that pass this set of tests have more comprehensive automated acceptance tests run against them. Once we have packages that pass all the automated tests, they are available for self-service deplyment to other environments for activities such as exploratory testing, usability testing, and ultimately release. Complex products and services may have sophisticated deployment pipelines; a simple, linear pipeline is shown below:

In the deployment pipeline, every change is effectively a release candidate. The job of the deployment pipeline is to catch known issues. If we can’t detect any known problems, we should feel totally comfortable releasing any packages that have gone through it. If we aren’t, or if we discover defects later, it means we need to improve our pipeline, perhaps adding or updating some tests.

Our goal should be to find problems as soon as possible, and make the lead time from check-in to release as short as possible. Thus we want to parallelize the activities in the deployment pipeline, not have many stages executing in series. There is also a feedback process: if we discover bugs in exploratory testing, we should be looking to improve our automated tests. If we discover a defect in the acceptance tests, we should be looking to improve our unit tests (most of our defects should be discovered through unit testing).

Get started by building a skeleton deployment pipeline—create a single unit test, a single acceptance test, an automated deployment script that stands up an exploratory testing envrionment, and thread them together. Then increase test coverage and extend your deployment pipeline as your product or service evolves.

Resources

-

A 1h video in which Badri Janakiraman and I discuss how to create maintainable suites of automated acceptance test

-

Lisa Crispin and Janet Gregory have two great books on agile testing: Agile Testing and More Agile Testing

-

Elisabeth Hendrickson has written an excellent book on exploratory testing, Explore It!. I recorded an interview with her where we discuss the role of testers, acceptance test driven development, and the impact of continuous delivery on testing. Watch her awesome 30m talk On the Care and Feeding of Feedback Cycles.

-

Gojko Adzic’s Specification By Example has a series of interviews with successful teams worldwide and is a good distillation of effective patterns for specifying requirements and tests.

-

Think that “a few minutes” is optimistic for running automated tests? Read Dan Bodart’s blog post Crazy fast build times

-

Martin Fowler discusses the Test Pyramid and its evil twin, the ice cream cone on his bliki.

FAQ

Does continuous delivery mean firing all our testers?

No. Testers have a unique perspective on the system—they understand how users interact with it. I recommend having testers pair alongside developers (in person) to help them create and evolve the suites of automated tests. This way, developers get to understand the testers’ perspective, and testers can start to learn test automation. Testers should also be performing exploratory testing continuously as part of their work. Certainly, testers will have to learn new skills—but that is true of anybody working in our industry.

Should we be automating all of our tests?

No. As shown in the quadrant diagram, there are still important manual activities such as exploratory testing and usability testing (although automation can help with these activities, it can’t replace people). We should be aiming to bring all test activities, including security testing, into the development process and performing them continually from the beginning of the software delivery lifecycle for every product and service we build.

Should I stop and automate all of my manual tests right now?

No. Start by writing a couple of automated tests—the ones that validate the most important functionality in the system. Get those running on every commit. Then the rule is to add new tests to cover new functionality that is added, and functionality that is being changed. Over time, you will evolve a comprehensive suite of automated tests. In general, it’s better to have 20 tests that run quickly and are trusted by the team than 2,000 tests that are flaky and constantly failing and which are ignored by the team.

Who is responsible for the automated tests?

The whole team. In particular, developers should be involved in creating and maintaining the automated tests, and should stop what they are doing and fix them whenever there is a failure. This is essential because it teaches developers how to write testable software. When automated tests are created and maintained by a different group from the developers, there is no force acting on the developers to help them write software that is easy to test. Retrofitting automated tests onto such systems is painful and expensive, and poorly designed software that is hard to test is a major factor contributing to automated test suites that are expensive to maintain.